Writing academic papers with org-mode

EDIT (2023-01-03)

I have recently migrated from Doom emacs to a vanilla emacs config. What I like about the vanilla config is that I am more in control of what it does. Doom emacs, in some respects, was a bit of a black box to me. Also, Doom emacs does a lot of things I do not actually need or want. In my original post, I linked to my dot files, which included my doom emacs config. The doom config files are still there, but not in the old_doom_config branch, instead of the master branch. My vanilla config maintains (I think) all of what I describe in my post. However, the config looks different in most places, for example because I could no longer make use of the Doom emacs macros.

EDIT (2021-08-10)

After upgrading my Doom emacs installation today, I noticed that org-roam-bibtex was broken. This has to do with the fact that org-roam-bibtex has recently switched over to org-roam V2, which has been in development for a while now and was released in July. Doom emacs now also supports org-roam V2 and one of the gibub pages for Doom emacs describes how you can make the switch. You have the option to stick with org-roam V1, but that version is no longer actively maintained. Making the switch to org-roam V2 basically involves changing a flag in your init.el file from +roam to +roam2. However, for org-roam-bibtex to work, you will need to make additional changes to your config (the config.el file). It is a good idea to check the new README at the org-roam-bibtex repository, as well as the manual. One of the more important changes is that org-roam-bibtex now uses an org-roam-capture template, instead of using its own capture templates.

You will also find that org-roam-server (a plugin that I did not discuss in the post below, but that I did occasionally use) does not work with org-roam V2. However, the author of org-roam-server points to an excellent alternative, called org-roam-ui. Make sure that you carefully follow the installation instructions for Doom emacs that are provided in the README of the repository.

You will find a working configuration in the doom folder of my dotfiles.

I also came across a blog post in which org-cite was announced. This is something I have not delved into yet, but when I briefly scanned the post, it seemed like org-cite is a more powerful ‘org-ecosystem’ citation solution. I have also read that the author of the org-ref mode started porting org-ref to org-cite with org-ref-cite. This is exciting stuff that I still need to look into.

Adding to what is already out there

I spent some hours in the past couple of days writing a paper on Q-SoPrA (finally), and I wanted a break from that. However, I am not very good at doing nothing, so my break consists of simply writing something else; something a bit lighter. I had thought about writing some posts about my workflow(s), so I thought I could use my break to start working on that. And then I thought it would perhaps be nice to write something about how I actually go about writing papers nowadays. That is what you’ll read about in the below.

I wrote this in a bit of a rush. I will revisit this post a couple of times to fix inevitable language mistakes and typos. It is also likely that some parts need further clarification.

The idea to write a post like this is not original. In fact, there is already a very helpful blog post on writing academic papers with org-mode that has helped me develop my own workflow for paper writing. At the same time, there is not much else that I could find. There were some things in the example linked above that did not really work for me and that I decided to do slightly differently. For some of this I had to cobble together some ideas from various pages where org-mode is discussed. One such page is of course the org-mode manual. Other pages include discussions I found on Stack Overflow and LaTeX Stack Exchange, but I don’t remember all the specific pages I consulted on this.

I wanted to write this post to provide another source of inspiration on how to use org-mode for academic paper writing, hopefully providing some additional snippets of information that you couldn’t already find tied together in another post.

The intended audience(s) and how they should read this blog post

I imagine that there are four possible types of audiences for the text below. I assume all these types consist of people that either work in academia, or have an interest in academia. Within that range, the five types of audiences I imagine would be interested in reading this post are:

- People that have no idea what org-mode is. The same people are unlikely to know what emacs is (org-mode was developed as an extension of emacs). People in this audience are probably used to writing their academic papers in office-like software, such as Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer. They may have found their way to this post because they’re interested in exploring something new. If you belong to this audience, I suggest that you keep on reading the first few parts of this post. If you’re still interested after that, keep on reading the rest.

- People that may have heard about emacs and org-mode, but haven’t given it a try yet. I imagine that some of these people currently write in LaTeX, or perhaps something like markdown. They may have found their way here while exploring alternatives to that. If you belong to this audience, I suggest you skim through the next part. There is a small bit where I briefly discuss some of the benefits of org-mode over LaTeX. I think LaTeX is awesome, but org-mode makes working with LaTeX a bit more pleasurable (at least for me). I should also add that I think writing academic papers with org-mode is a lot easier if you already have some experience with LaTeX.

- People that already work with emacs, perhaps also with org-mode. Maybe these people already use org-mode to organize their to-do lists and agendas, but they haven’t used org-mode yet to write papers. Or maybe they do write papers with org-mode, but they are simply interested in reading how others organize their paper-writing-workflow. If you belong to this audience, I suggest to skip over to the part where I discuss my setup in detail. I hope you’ll find something useful there.

- People that are emacs and org-mode veterans that come here to cringe at an attempt at an informative post by someone with limited experience with emacs and org-mode. If you belong to this audience I don’t expect you’ll learn anything new from this post, but maybe you want to help me out. In that case, just skim through everything and if you see me write dumb stuff, feel free to point it out by dropping me an email.

Okay, I guess there is actually a fifth audience, which would be the people that know emacs, but dislike it because it is bloat. If you belong to that audience, you could skim through the next bit, where I dedicate about 2 sentences to this discussion, and then direct your hate mail to my email address.

Start here if you don’t know what emacs is

Let’s start with emacs. I find it tricky to accurately describe what emacs is, because, in a way, it is many things at the same time, depending on how you set it up and use it. However, I think I would settle on a description of emacs as a lisp-interpeter, as well as an ecosystem of tools that together constitute an integrated development environment. Emacs can be configured and extended with a dialect of lisp, which is a programming and scripting language (you’ll see plenty of that in snippets below). I use emacs to write software, to read my email, to organize my to-do lists (actually, this is an org-mode thing that I won’t discuss here), to keep notes on papers, to keep a journal with ideas that I am afraid I would otherwise forget about, and several other things. It is usually the first thing that I load up after booting into Linux and probably the software that I spend most time ‘in’. Emacs has been around for a long time and is still being actively developed today, which I believe is testimony to its incredible power.

There are plenty of Linux-enthusiasts that don’t like emacs at all, for example because they feel it goes against the UNIX philosophy that software tools should “do one thing and do it well”. In other words, in their opinion emacs is bloat. As I mentioned before, emacs does indeed try to be a lot of things at the same time. However, in the above, I consciously described emacs as “an ecosystem of tools”, because I think emacs can be seen as a collection of lisp-based tools that each do one thing (and do it well), but that can interact in various ways to make them do whatever you want emacs to do. I think you could even use emacs as a kind of Operating System if you wanted (I am not sure why you would, though). The benefit of having all these tools work together in one ecosystem is that they often work together well ‘out of the box’.

Emacs is highly configurable, so there are many different ways in which Emacs can be set up. Obviously, I am not going to discuss all of that in detail. What I do want to note here is that I use a particular ‘flavor’ of emacs that is known as Doom emacs. Doom emacs has a number of benefits over ‘vanilla emacs’, such as a tight package management system and a pre-configured setup that just does a lot of things ‘right’. I also like that it makes use of evil-mode, which more or less means that it works with vim keybindings. However, that is a story for another time.

Org-mode as a powerful extension of emacs

Org-mode is a popular extension of emacs which revolves around a flexible structured plain text format. You can use it to manage to-do lists, for agenda and/or project management, to keep notes, as well as a wide range of writing applications (among others!). Org-mode has an ecosystem of its own, which means that it is highly extensible itself. For example, in the below I write a few things about org-ref, org-noter and org-roam, which all play a role in my writing process. I combine these tools with others that are not specifically org-mode-related. For example, to read pdfs in emacs, I make use of pdf-tools, and I use helm-bibtex (in combination with Zotero) to navigate my library of publications and find citations to insert. I will discuss all of that in more detail further below.

But let’s take a few steps back first. So, org-mode is a flexible structured plain text format, one that includes a markup language similar to that of markdown (which is the markup language in which I am writing this blog post right now). What does that mean? Well, I can do things like encapsulating text in asterisks (*) if I want to make that text bold and encapsulating text in forward slashes (/) if I want to make that text italic. I can make headings by starting a line with an asterisk followed by a space. If I want to make a heading at a lower level, I simply add more asterisks. I can also make (numbered) lists and these can be nested. And this is only the simple stuff. As an example of something more advanced, org-mode offers very powerful support for tables. You can even use formulas in tables, similar to what you can do in Microsoft Excel or LibreOffice Calc.

All of that in plain text.

A typical org file might look something like the following:

* This is a level 1 heading

** This is a level 2 heading

A paragraph doesn't necessarily need any markup language.

You could write each sentence on its own line.

Upon exporting, these lines will be put together in a paragraph.

To start a new paragraph you simply insert an empty line before it.

Lines of text that don't have empty lines between them are treated as a single paragraph.

Text can be *bolded* or in /italic/, among other things, using simple markup.

- This is a list entry

- This is another list entry

+ Lists can be nested.

We can also have numbered lists, like so:

1. This is a numbered list entry

2. Here is another one.

a. Of course we can also nest numbered lists.

I don't actually have to type all these numbers.

When making a list, I simply press CTRL+Return to add a new entry to the list.

I can press the TAB button to indent the list (make a nested entry).

To make a table, we can simply encapsulate text in lines and pipe symbols:

|--------------------+--------------------------|

| *This is a header* | *This is another header* |

|--------------------+--------------------------|

| This is a cell | This is another cell |

|--------------------+--------------------------|

| And so on... | |

|--------------------+--------------------------|

When altering an entry in a table, I can move to another cell by pressing tab, and the table will

automatically be reformatted to look 'fancy' again.

New cells will also be added upon pressing tab if your cursor is in the bottom-right cell.After writing a document in org-mode, you’ll often want to export them to some other format. Org-mode in emacs provides a powerful exporting engine for this, but you could also use pandoc. With emacs’ export engine, you can, for example, export an org-mode document to a beautifully formatted pdf. In the process, the document will first be exported to TeX as an intermediary step, so if you are familiar with LaTeX, you’ll know what nice outputs you could make with org-mode in this way.

Wait! Why on earth would you want this?

Some of you might think: “What’s the point? What benefit does this give you over Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer, in which you can do most of these things?” You might also think that plain text looks ugly (I don’t; I’ve come to love it) and you’d rather see what you get, as you do in Microsoft Word, rather than first having to export to some other format before you see what it’ll eventually look like.

Know that there are certain benefits to working in a plain text format like the org format. First, it makes version control much easier. For example, I use Github for version control, which means that after each time I that I add bits and pieces to a paper (usually at the end of the day), I push a commit to github. This allows me to keep track of all the changes I make between versions, without having to explicitly save a new version of my document whenever I want to make a new version, and without the risk of accidentally overwriting changes that I might later regret. If you want to know more about this approach to version control, there are plenty of places to read more about it, such as here. One thing to note is that this approach to version control only works well if you work in plain text.

Note that, with "version control", I mean something different than simply saving changes to your document on a regular basis. You should of course always do that to ensure that you don't accidentally lose a lot of work. My purpose with versioning of papers is not to keep track of each and every small change that I make, but to keep track of the larger chunks of text that I change over time. I might decide that a certain idea doesn't work well and that I want to revert to an alternative idea that I tried earlier. In that case it is nice to know that I have a version of that somewhere on my Github repository.

Second, as I mentioned previously, you can export org-formatted documents to many other formats, including odt, docx, TeX, and (via TeX) pdf. You don’t get this kind of flexibility with Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer. Moreover, because the text is plain text with some simple markup added to it, it is relatively easy anyway to reuse the text in another format. This could just be a matter of slightly changing the markup. However, I would just use pandoc for this most of the time.

Third, since you’re working in plain text, you don’t need a dedicated editor. Sure, writing org-mode in emacs makes a lot of things easier, but in principle there is nothing to stop you from using any other text editor. This means that you don’t depend on one or a few software packages. Also, because (again) we are working in plain text, it is unlikely that at some point you won’t be able to open your document anymore because it was written with outdated software. I guarantee you that plain text editors will be around for a loooooooong time.

That being said, my purpose with this post is not to convince you of using org-mode. In fact, there are plenty of downsides to it too. For me, one of the most important ones is that none of my colleagues works with org-mode. In fact, I doubt they ever heard of emacs or org-mode. This is of course unproblematic if you mostly write by yourself, but it is problematic if you frequently write with others, which is true for me. This downside is compounded by the fact that my university more or less forces you to work with Windows and Office365, unless you choose to work on your own machine. The result is that everybody is socialized into using the same set of tools, and trying to work around this quickly becomes cumbersome.

However, despite these downsides, I find myself using org-mode whenever I can. I like the fact that I can just focus on writing without too many distractions. I also like the fact that, with a few keystrokes, I can…

- find papers to consult.

- then read the pdfs of those papers in the same software that I use for writing.

- add a citation to a paper.

- open the pdfs attached to any of my citations.

- quickly consult my notes on other papers (made with org-noter), or other notes that I made, for example with org-roam.

- export my work to different formats, such as docx or pdf, where they immediately look nicely formatted without doing extra work.

- completely change that formatting by altering just a few lines of export settings.

- have auto-generated and -formatted bibliographies based on the citations I included in my paper.

- easily include figures in my paper (including pdfs of figures) without having to worry about where exactly to place them (this is something I really hate about Office programs).

- Include TODO notes in my papers that show up in my agenda.

- use the very powerful vim-keybindings.

There might be things I forget right now. More generally speaking, I somehow find working in emacs and org-mode much more satisfying than working in Word, and I often find myself looking for ways to work around Office-based programs more than I already do.

Why don’t you just use LaTeX?

Some of the things I outline above are things that others use LaTeX for. I already mentioned you can make beautifully formatted text with LaTeX and org-mode exports to pdf via TeX. So why wouldn’t you just work in LaTeX directly?

Well, I love LaTeX, and I worked in it for a while, but LaTeX markup is quite elaborate and, in my opinion, a bit distracting. I often found myself going back to tex documents that I wrote earlier, for example to remember how I got my figures to come out the way I liked it. Org-mode’s markup is much cleaner and intuitive. Also, if you really want to just insert ‘plain’ LaTeX in some places, you an easily do that. You could say that org-mode makes working with LaTeX a lot easier.

Also, exporting to pdf from org-mode takes just one command. In LaTeX you would need to run a LaTeX compiler, then typically BibTeX to resolve the linkages to citations, then the LaTeX compiler again… When you export to pdf from org-mode, all that needs to be done as well, and you actually add additional steps because it first needs to export from org to tex. However, emacs does all of this for you in the background. You don’t need to worry about it.

Org-mode does not provide the possibility to directly export to docx. You can of course export to odt and then save your file as docx. However, I've noticed that exporting from org-mode to odt does not work well if you want to include a bibliography. I think the easiest way to convert from org tot docx is to use pandoc. If you use the `--citeproc` argument, you can also get the bibliography exported properly.

My setup (start here if you skipped over the first parts)

So let’s get into the details of my setup. I’ll (roughly) discuss the following:

- Setting up an org-mode document for exporting to LaTeX

- Citation management

- Managing notes that you might use for your papers.

Please note that some snippets of my emacs config file below will only work for you if you use Doom emacs. My config file makes use of macros that are specific to Doom emacs, such as `after!`. However, if you are familiar with emacs, and you don't want to use Doom emacs, it should be relatively easy to adjust my examples.

A template for papers

I made a template for papers that I can reuse. The template looks more or less like the below.

#+TITLE: Your title goes here

#+OPTIONS: toc:nil author:nil

#+LaTeX_CLASS: apa6

#+LaTeX_CLASS_OPTIONS: [a4paper]

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \author{author name}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \affiliation{author affiliation}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \leftheader{With the apa6 class, it is good idea to customize the left header here}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \shorttitle{Your short title goes here}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \usepackage{breakcites}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \usepackage{apacite}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \usepackage{natbib}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \usepackage{paralist}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \let\itemize\compactitem

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \let\description\compactdesc

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \let\enumerate\compactenum

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \abstract{Your abstract goes here}

#+LaTeX_HEADER: \keywords{Your keywords go here}

* Introduction

And now just type away!

# Everything with a "# " (don't forget the space) before it is a comment and is ignored when exporting to pdf.

** This is a sub-heading!

Remember our lists?

- Here is a list entry

- Here is another one

# Don't forget to add the bibliography by the end.

bibliographystyle:apacite

bibliography:/path/to/library.bibSo, what do we have here? At the top of the file we see a kind of preamble. Org documents often include some export settings in their preamble. I call this a preamble, but you can actually put these export settings anywhere in your file.

Note that a lot of my export settings are actually LaTeX headers. This is the kind of stuff that you would also put in your LaTeX preamble, which org-mode can handle for you in this case. I use these LaTeX headers to set the document type (apa6 class article, in this case), some options related to the types of citations I use, some options that are apa6 class specific, and some options to change the default behavior of the LaTeX formatting process.

Some of these options were adopted from the example set here, such as the use of \usepackage{breakcites} to allow citations to word wrap, \usepackage{paralist}to make lists more compact (the three lines directly below this are related to this too), and \usepackage{apa6} for apa-compliant citations. I added \usepackage{natbib} to allow for natbib-style citation markup (see further below).

The apa6 LaTeX class specification uses the \abstract{} command to include an abstract and the \keywords{} command to include keywords. The class also natively supports multiple ways to report authors and affiliations. In the template, you’ll see what you’d need to include if you are the sole author of the paper. If you have two authors, you could instead use \twoauthors{Author One}{Author Two}. For more authors, you follow the same logic \threeauthors{}{}{} and so on (this class currently supports up to six authors). The same goes for affiliations: For two authors you can use \twoaffiliations{}{}. I noticed that the left header only shows the first author by default. I therefore included the \leftheader{} command so I can just customize it. The \shorttitle{} will be shown as the right header.

You can also specify the author name with org-mode’s own #+AUTHOR export option, but I found that it quickly becomes a pain to handle authors and affiliations properly when there is more than one author. I therefore use the LaTeX headers for this instead. In that case, it is necessary to include author:nil in #+OPTIONS, because emacs may default to using the username specified in your config file as the author name, even if you didn’t include #+AUTHOR in your file. In that case, you will always be included as a co-author, alongside any other authors that you already specified in the LaTeX headers.

I also set toc:nil to prevent a table of contents from being included.

You should make sure to include your bibliography by the end of your document. The bibliography will appear right where you put the following lines:

bibliographystyle:apacite

bibliography:/path/to/library.bibFigures and tables

One thing that org-mode makes very easy to do is to add figures and tables to your paper. As I mentioned before, with LaTeX I often had to look up how to do those things properly. Org-mode is just much more intuitive in its use here.

To include a figure, you basically just need to include a link to it. In org-mode, a link is always placed between double brackets (as shown below). You can add a caption for your figure, as well as a name that you can use for reference above the link to the figure. If you are using a multi-column document class (like apa6) and you want figures to span the full width of the page, instead of just one column, you also want to add the third option (ATTR_LATEX: :float multicolumn) that I have added below.

#+CAPTION: Your figure caption goes here

#+NAME: fig:shortname

#+ATTR_LATEX: :float multicolumn

[[path/to/your/figure]]The name variable comes in useful whenever you want to refer to the figure in your text. This is something else that I find painful to do in (for example) Word documents. If you refer to your figures by numbers in your text, you have to be careful to update these numbers if something changes in the order of figures. In org-mode, you can instead refer to your figures by their label, using an internal link, and this link will automatically be resolved to a number upon exporting. So, for example, you could write something like the following in your text:

See figure [[fig:shortname]] below.And if that figure happens to be the third figure in your document, then in the exported pdf document this will resolve to:

“Please see figure 3 below.”

For tables, you can simply use org-mode’s built-in table functionality, and when exporting tables will be formatted according to the specifications of whatever you’re exporting to.

There are various ways in which you can configure the way tables come out too. As with figures, you’d place these export options above your table.

Setting up the LaTeX class in your config file

With the information above you already know most of the basics required for writing a document in org-mode that can be exported as a pdf (via LaTeX).

For the exporting via LaTeX to work properly, you’ll need to set up the LaTeX classes that you plan to use, which you do in your emacs config.el file. This is just something I shameless copied from the example that I’ve mentioned a few times before, and it works well for me.

;; Set up org-mode export stuff

(add-to-list 'org-latex-classes

'("apa6"

"\\documentclass{apa6}"

("\\section{%s}" . "\\section*{%s}")

("\\subsection{%s}" . "\\subsection*{%s}")

("\\subsubsection{%s}" . "\\subsubsection*{%s}")

("\\paragraph{%s}" . "\\paragraph*{%s}")

("\\subparagraph{%s}" . "\\subparagraph*{%s}")))From what I understood from the explanation offered here, this maps the org-mode headings and lists (and so on) to their LaTeX equivalents.

Using citations in your paper

In the above we have the basics more or less covered, such as including export settings and knowing how to format a basic org file, including figures and tables. We also know how to include our bibliography, but an important topic that we haven’t covered yet is how to include citations in your document in the first place.

The org-mode ecosystem includes a wonderful tool for this, which is org-ref. Org-ref depends on helm-bibtex. Helm-bibtex is a wonderful tool that you can use to browse your library of references from within emacs. If you use a citation management tool like Zotero, it is easy to keep a library of references that also have pdfs linked to them. You can export the library as a .bib file, which can then be read by helm-bibtex. Org-ref uses the helm-bibtex menu to search for citations that you want to insert. If you have org-ref installed, you can use the C-c ] keybinding to insert a citation at point. You will then be shown a list of the references included in the .bib-file that you pointed helm bibtex to (see below). The list is filtered as you type. When you press enter on any reference, it will be included in your paper. For an example, see the citation by the end of the snippet below.

For example, if the study focuses on explaining the emergence, development and/or decline of an entity,

it makes sense to adopt a strategy in which one defines that entity as a central subject

and than focuses on reconstructing the events that this central subject endures or makes happen citep:Hull1975.This gives a good idea of how org-ref citations are formatted. They basically use the natbib format. For example:

- cite:Spekkink2016 becomes “Spekkink (2016)”;

- citep:Spekkink2016 becomes “(Spekkink, 2016)”;

- citeyearpar:Spekkink2016 becomes “(2016)”;

And so on…

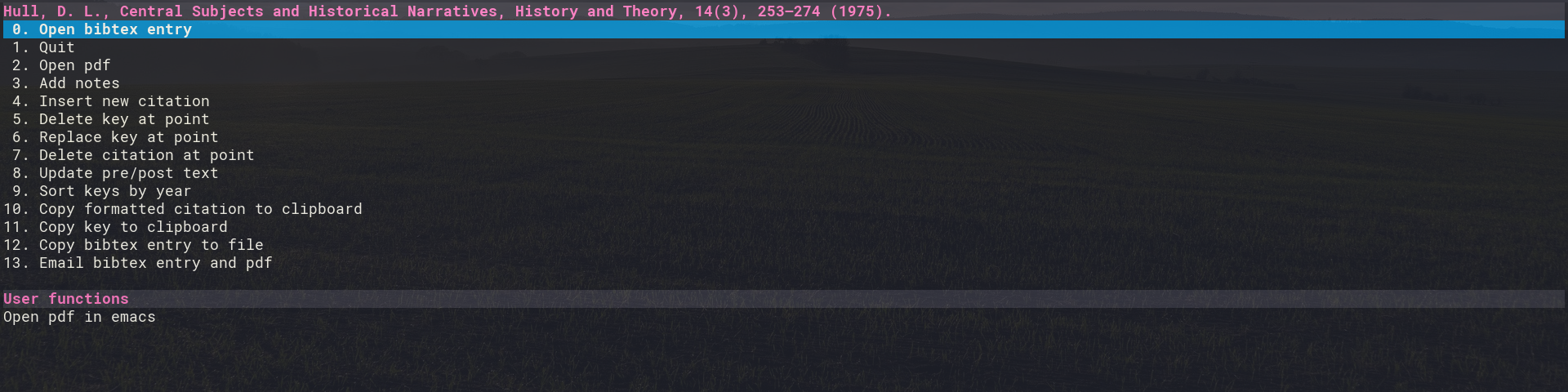

What the snippet above doesn’t show, is that the citations in org-mode behave a bit like links. You can place your cursor on them, press return, and you’ll be shown a helm-bibtex menu as shown below (click the picture to view a larger version of it):

You’ll see that you can do a number of things related to this citation, such as opening the pdf to re-read something if you need to. You can also access your notes on this paper from here (see more on that further below), you can add pre- or post-text, and a number of other things.

For org-ref and helm-bibtex to work properly, you’ll need to put some things in your emacs config.el file. See my configuration below (and notice the comments):

;; helm-bibtex related stuff

(after! helm

(use-package! helm-bibtex

:custom

;; In the lines below I point helm-bibtex to my default library file.

(bibtex-completion-bibliography '("~/Zotero/bibtex/library.bib"))

(reftex-default-bibliography '("~/Zotero/bibtex/library.bib"))

;; The line below tells helm-bibtex to find the path to the pdf

;; in the "file" field in the .bib file.

(bibtex-completion-pdf-field "file")

:hook (Tex . (lambda () (define-key Tex-mode-map "\C-ch" 'helm-bibtex))))

;; I also like to be able to view my library from anywhere in emacs, for example if I want to read a paper.

;; I added the keybind below for that.

(map! :leader

:desc "Open literature database"

"o l" #'helm-bibtex)

;; And I added the keybinds below to make the helm-menu behave a bit like the other menus in emacs behave with evil-mode.

;; Basically, the keybinds below make sure I can scroll through my list of references with C-j and C-k.

(map! :map helm-map

"C-j" #'helm-next-line

"C-k" #'helm-previous-line)

)

;; Set up org-ref stuff

(use-package! org-ref

:custom

;; Again, we can set the default library

(org-ref-default-bibliography "~/Zotero/bibtex/library.bib"))

;; The default citation type of org-ref is cite:, but I use citep: much more often

;; I therefore changed the default type to the latter.

(org-ref-default-citation-link "citep")

;; The function below allows me to consult the pdf of the citation I currently have my cursor on.

(defun my/org-ref-open-pdf-at-point ()

"Open the pdf for bibtex key under point if it exists."

(interactive)

(let* ((results (org-ref-get-bibtex-key-and-file))

(key (car results))

(pdf-file (funcall org-ref-get-pdf-filename-function key)))

(if (file-exists-p pdf-file)

(find-file pdf-file)

(message "No PDF found for %s" key))))

(setq org-ref-completion-library 'org-ref-ivy-cite

org-export-latex-format-toc-function 'org-export-latex-no-toc

org-ref-get-pdf-filename-function

(lambda (key) (car (bibtex-completion-find-pdf key)))

;; See the function I defined above.

org-ref-open-pdf-function 'my/org-ref-open-pdf-at-point

;; For pdf export engines.

org-latex-pdf-process (list "latexmk -pdflatex='%latex -shell-escape -interaction nonstopmode' -pdf -bibtex -f -output-directory=%o %f")

;; I use orb to link org-ref, helm-bibtex and org-noter together (see below for more on org-noter and orb).

org-ref-notes-function 'orb-edit-notes)Some of this configuration involves pointing helm-bibtex and org-ref to my default library.bib file. I also had to add several lines to make sure that (1) helm-bibtex knows where to find the path to pdf files in the library.bib file, (2) org-ref is able to find the pdf file associated with the citation that I have my cursor on and (3) org-ref is then able to open that file. I am not entirely sure, but I believe the default behavior was for org-ref to open the pdf in an external viewer. My configuration also makes org-ref open pdfs in emacs instead.

Using pdf-tools

Since I’ve mentioned the possibility to open pdfs a couple of times, this as a good a place as any to bring up that I use pdf-tools to read pdfs instead of emacs’ default doc-viewer. In pdf-tools, pdfs look much better than in doc-viewer. In addition, pdf-tools comes with some annotation tools, although I don’t use those myself.

To use pdf-tools as the default viewer, you can add the folowing lines to your config (keep in mind that the below is specific to Doom emacs configs):

;; This is to use pdf-tools instead of doc-viewer

(use-package! pdf-tools

:config

(pdf-tools-install)

;; This means that pdfs are fitted to width by default when you open them

(setq-default pdf-view-display-size 'fit-width)

:custom

(pdf-annot-activate-created-annotations t "automatically annotate highlights"))Consulting notes on papers

So far, so good. We now know how to write basic documents in org-mode, and we’re able to use org-ref (with helm-bibtex) to insert and alter references, and to open the pdf files associated with them.

Let’s stick with org-ref and helm-bibtex for a bit longer. Let’s say that you’ve kept notes on the papers that you want to cite in your own paper. You might want to consult those notes while writing. Here too, I find it convenient to be able to do this within the program that I am doing my writing in. That is why I use org-noter to keep notes on my papers, and I use org-roam-bibtex (orb) to link org-noter and helm-bibtex together. This is a topic that is discussed in detail in this blog post, so I won’t cover everything in detail here.

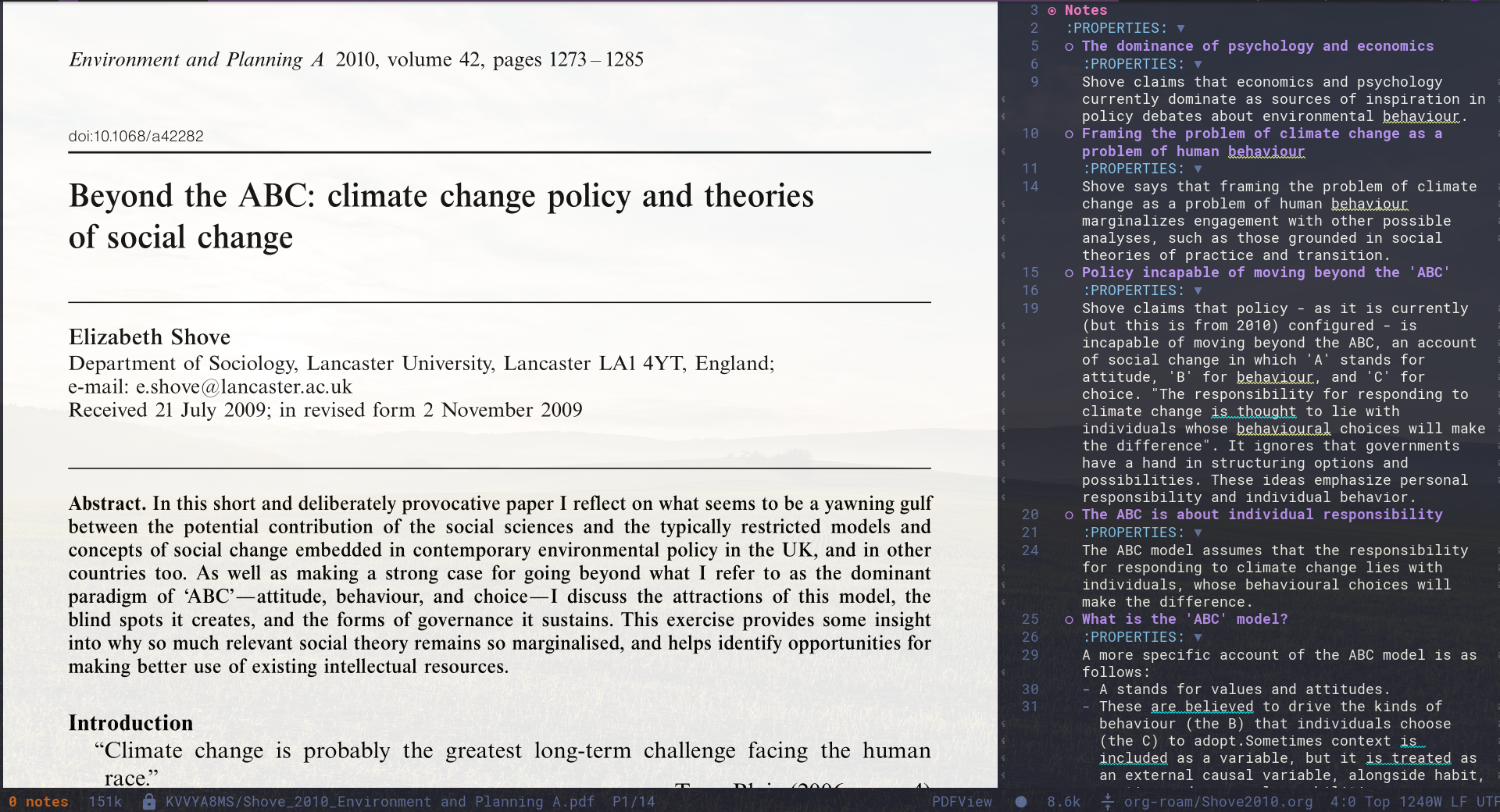

Very briefly then: org-noter is an emacs package that you can use to keep notes on pdfs in an org document. It works together quite well with the pdf-tools package that I mention above. Basically, with org-noter you can read a pdf, and have your notes document open beside it. You can write notes that are associated with particular pages in the pdf document, as well as notes that are associated with particular locations on pages. If you then browse through your notes, org-noter will automagically bring up the page (or location) of the pdf document that the note is associated with. It looks a bit like this:

In the image, you see the pdf on the left, and you see the notes I wrote on this pdf on the right. Each of those notes is related to a particular location in the document, which I can find back easily by jumping back and forth between my notes.

See my org-noter configuration below:

;; org-noter stuff

(after! org-noter

(setq

org-noter-notes-search-path '("~/org-roam/")

org-noter-hide-other nil

org-noter-separate-notes-from-heading t

org-noter-always-create-frame nil)

(map!

:map org-noter-doc-mode-map

:leader

:desc "Insert note"

"m i" #'org-noter-insert-note

:desc "Insert precise note"

"m p" #'org-noter-insert-precise-note

:desc "Go to previous note"

"m k" #'org-noter-sync-prev-note

:desc "Go to next note"

"m j" #'org-noter-sync-next-note

:desc "Create skeleton"

"m s" #'org-noter-create-skeleton

:desc "Kill session"

"m q" #'org-noter-kill-session

)

)The most important thing is that you need to tell org-noter what the default location of your notes is. In my case, I include my notes in my org-roam folder (we’ll discuss org-roam soon). I also added a bunch of keybinds that I use to insert and navigate notes.

Org-noter doesn’t integrate with helm-bibtex out of the box. That is what you can use orb for. One very important thing that orb does is to tell helm-bibtex to use org-noter as the default note-keeping package. It also integrates org-noter with org-roam (again, we’re getting to org-roam soon).

See my config snippet for orb below. It is an altered version of what I copied from another post about this.

;; org-roam-bibtex stuff

(use-package! org-roam-bibtex

:hook (org-roam-mode . org-roam-bibtex-mode))

(setq orb-preformat-keywords

'("citekey" "title" "url" "author-or-editor" "keywords" "file")

orb-process-file-keyword t

orb-file-field-extensions '("pdf"))

(setq orb-templates

'(("r" "ref" plain(function org-roam-capture--get-point)

""

:file-name "${citekey}"

:head "#+TITLE: ${citekey}: ${title}\n#+ROAM_KEY: ${ref}

- tags ::

- keywords :: ${keywords}

* Notes

:PROPERTIES:

:Custom_ID: ${citekey}

:URL: ${url}

:AUTHOR: ${author-or-editor}

:NOTER_DOCUMENT: ${file}

:NOTER_PAGE:

:END:")))The first few lines are basically required to get orb to work with org-roam.

The most important lines are the ones below that. The orb-templates function basically creates the templates of the files that you use to record your notes on pdfs with. I only have one template and at the bottom of the snippet you’ll see what is included in it (e.g., a url to the file, the author). You have to define the keywords included in the template with the orb-preformat-keywords function.

With these settings, if I navigate to a reference in helm-bibtex, and then tell helm-bibtex to open my notes on that reference, it will create a new file (if a file on that reference does not already exist) which is preformatted according to the template defined above.

In other words, whenever I am writing a paper, I can easily consult my notes on another paper by opening up helm-bibtex, navigating to the paper I want to consult the notes on, and then pressing F9 (or simply choosing ‘‘add notes’’ from the helm-bibtex menu). Combined with the things I mentioned earlier: For any citation in my paper I can quickly open the pdf of that citation as well as my notes on that paper within a few seconds, and all within the same program.

Org-roam

Not all notes that are relevant to the paper I am writing are necessarily notes on ‘another paper’. They might just be notes on an idea that I wrote up a while ago. They might also be more elaborate notes that I kept on a certain topic and that relate to multiple papers at the same time. I might want to consult these notes too.

In addition, I might want to be able to link my notes on one paper to notes that I made on another paper, or to notes that I wrote on a broader topic.

This is (more or less) where org-roam comes in. There is a lot to be said about org-roam itself, but I don’t want to get lost in the details here. Briefly, org-roam allows you to build a kind of ‘second brain’. It is an approach to taking notes that makes use of the Zettelkasten method. The idea behind that method is more or less that you keep relatively short notes that you explicitly link to other short notes. Together, the notes form a horizontal network of notes that can be quickly navigated.

So, whenever you are writing a note on something, you will want to link it to notes on other ideas that you think are associated to the topic you are currently writing a note on. An excellent discussion of that principle is offered here.

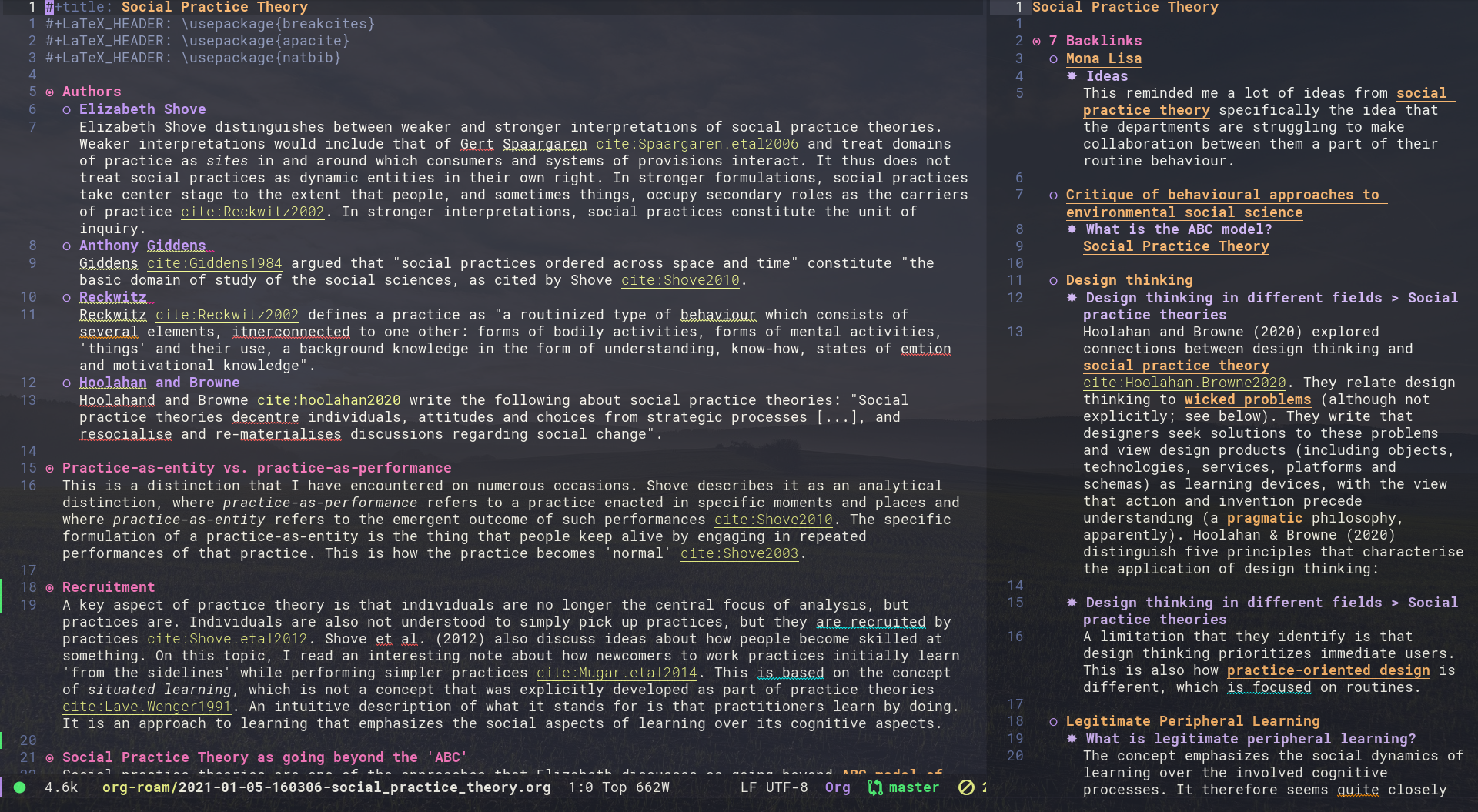

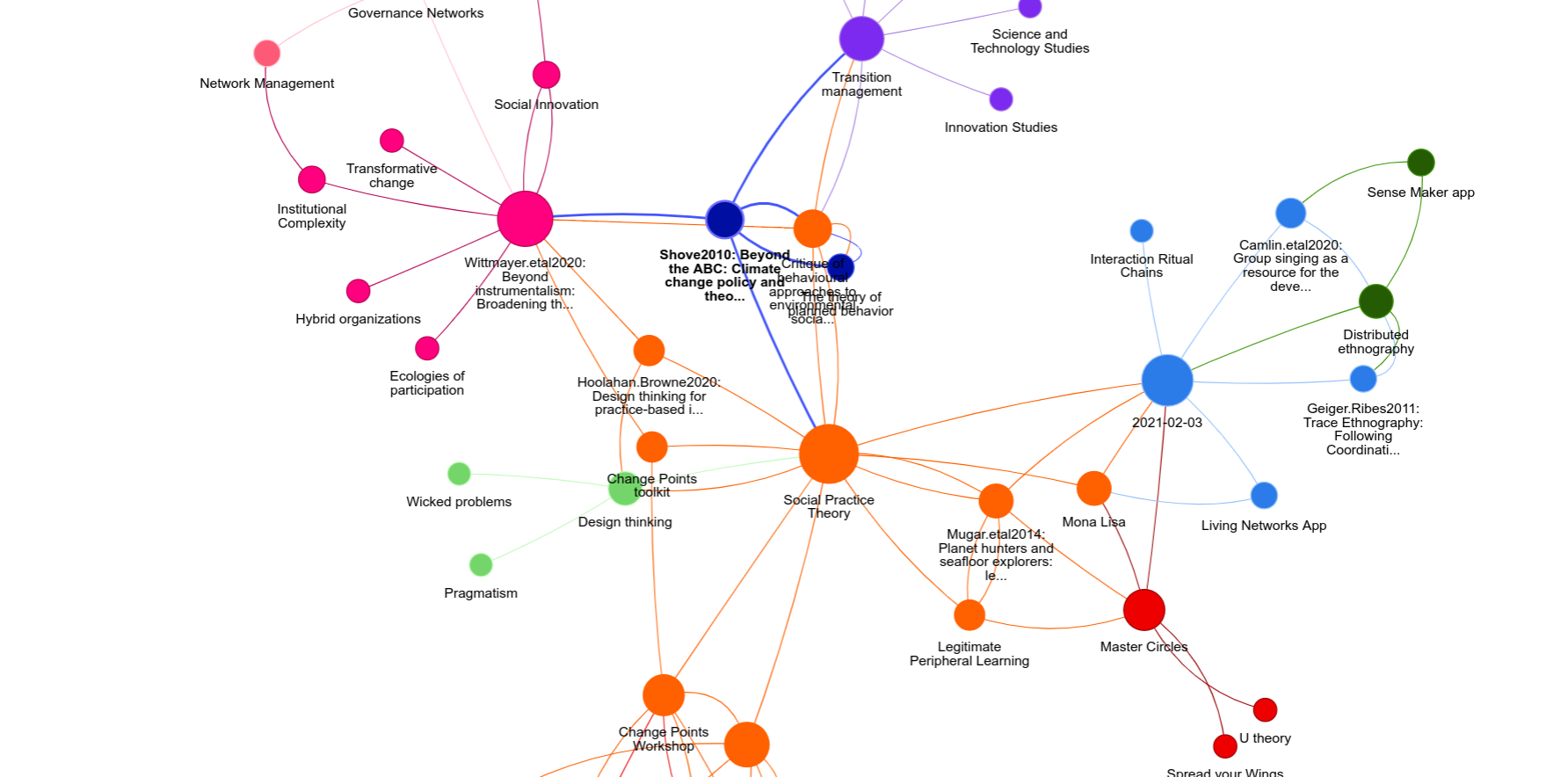

Org-roam itself provides a powerful infrastructure that implements this approach to note-taking. A key element of it is the use of a buffer that gives you an overview of all the notes that are linked to the note you are currently inspecting (see below for an example; the overview buffer is on the right).

If you keep this approach to note-taking up for a while, you’re slowly but surely building a network of notes. Basically, you are building your own wiki.

My network of notes includes notes on various broader topics (such as the notes on social practice theory of which I included a screenshot above), notes on projects that I am working on, notes that I took on a particular day (e.g., ideas I didn’t want to forget about or perhaps notes on a meeting I had on that day), and of course my notes on papers.

What makes org-roam so powerful is that you can quickly (re)trace the associations between ideas that you made notes on. You might open a document with notes that you made on a particular paper, then follow the links to other notes that might seem interesting for whatever you are currently writing on, and so on and so forth.

This could even be a viable approach to outlining your initial ideas for a new paper, similar to what is shown in this video, which uses the software that inspired org-roam.

See my basic org-roam config below.

;; org-roam related things

(after! org-roam

(setq org-roam-directory "~/org-roam")

(add-hook 'after-init-hook 'org-roam-mode)

;; Let's set up some org-roam capture templates

(setq org-roam-capture-templates

(quote (("d" "default" plain (function org-roam--capture-get-point)

"%?"

:file-name "%<%Y-%m-%d-%H%M%S>-${slug}"

:head "#+title: ${title}\n"

:unnarrowed t)

)))

;; And now we set necessary variables for org-roam-dailies

(setq org-roam-dailies-capture-templates

'(("d" "default" entry

#'org-roam-capture--get-point

"* %?"

:file-name "daily/%<%Y-%m-%d>"

:head "#+title: %<%Y-%m-%d>\n\n"))))What I do here is to first point to my org-roam directory, which is a folder without any sub-folders (except for one subfolder in which I keep my ‘daily’ notes, which are structured more like a journal) where I keep all my notes (including the ones made with org-noter). I make sure that org-roam runs on emacs startup, and then I define two kinds of templates. These templates define the names of the files to keep your notes in, as well as the basic contents of these files.

The first template is the template for my general notes. These notes are kept in files with the date and time of their creation, followed by a short title that I type when creating the note. The file itself only includes a title, and nothing else.

The second template is the template for my org-roam-dailies, which is basically a journal-type note, associated with a particular date. These files simply have the date on which they were made as their filename, and in this case too, the file itself includes nothing but the title of the file.

Whenever I am writing notes in one of these files, I can use simple keystrokes to insert links to other notes. If I insert a link to a note that doesn’t already exist, then a new file is automatically created for that note, ready to be filled at some point.

Wrapping up

This lengthy blog posts discusses some of the key elements involved in my current paper writing process. In short, org-mode serves as its basis, but this basis is enriched with powerful tools that allow me to:

- export to different kinds of filetypes, including beautifully formatted pdfs.

- insert citations to papers in my library that are relevant to what I am currently writing on.

- read the pdfs of those papers.

- consult my notes on those papers, or write new ones.

- consult other notes that may be relevant to what I am working on that are not tied to specific papers.

- find even more potentially relevant notes, based on the links that exist between notes.

I hope you found something useful / interesting in this post!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: