Retrieval augmentation with literature

Intro

In the summer, I started a series of posts on using the LangChain framework. This is the second post in that series. In the first post I introduced the idea of retrieval augmentation and vector stores and I explained the Python scripts that I use to create and update vector stores. In this post I go into the actual use of retrieval augmentation. The example I focus on here is the use of retrieval augmentation to chat with OpenAI’s Large Language Models (LLMs) about the literature on my Zotero library.

Chainlit

The initial LangChain tools that I built were simple command-line tools. I soon discovered a framework called Chainlit, which allows you to use you browser as an interface for your LangChain apps, and it comes with several other goodies. To be able to follow along with the examples below, you will need to install the Chainlit Python module. Chainlit is in development and future updates might break some of the things that I showcase in this post. The version of Chainlit that I have installed at the time of writing this post is 0.7.1.

A short recap

Without going into too much detail, a short recap of the idea of retrieval augmentation might come in useful. Our goal is to chat with LLMs about the contents of the literature in our Zotero library. This is useful for multiple things, such as quickly consulting our literature on concepts that we are interested and finding back the papers in which these concepts are described, but that we may have forgotten about. Given that can have a conversation with an LLM about our literature and that the LLM to some extent memorizes what has been said before in the conversation, we can even chat with LLMs about the relationships between concepts. I use this tool, for example, to quickly create notes on concepts that I can integrate in my writings. I also use it when preparing for teaching, for example to quickly compile lecture notes with additional background on the concepts and theories that I am teaching about. We can do this with the help of retrieval augmentation. When we ask a question, our question gets embedded, that is, it gets converted into a coordinate in a semantic space that we have populated with fragments of texts from the papers we wish to chat about. These fragments are stored in our vector store (see my previous post on this topic). Our tool retrieves fragments of text that have content that is semantically similar to our question. Our tool then includes these fragments of text as context in our question, allowing the LLM we interact with to use this knowledge to answer our question.

The script that I detail below assumes that you have already created a vectorstore that contains the literature from your Zotero library (again, see my previous post on this topic).

Folder structure and files

Let us start with the folder structure for our tool. In our main folder, we create two subfolders:

- answers

- vectorstore

One thing that we can do with retrieval augmentation is to record the actual fragments of text that our tool retrieved, as well as details of the sources that these fragments were retrieved from. I find this extremely useful, because it allows us to have our tool cite its sources, so that we can double check its output. To this end, I have my tool write log files in to the answers folder. Whenever I start a new chat session, a new log file is created in which the tool records the questions I ask, the answers it gives and then the fragments of text that it used to come to this answer as well as the sources that these fragments are from.

The ‘vectorstore’ folder simply contains the vector store that contains our literature.

In the main folder we also have a few files:

- ask_cl.py: The actual script that I detail below. You can of course give this another name.

- constants.py: A Python file that just contains our API key (which we do not want to expose, because we do not want to share it with others)

- chainlit.md: This gets created automatically when you run a chaintlit app for the first time. It is a simple readme file that is shown everytime you run your chainlit app and that you can of course adjust to your own needs and wants.

You might have several other files in the folder, such as scripts that I described in my first post of this series. However, the ones listed above are the only ones we really need to make the examples below work.

My script

The modules that we import

Let us go over the main script now: the ask_cl.py script. We’ll first import all the modules that our tool will make use of.

from langchain.chains import ConversationalRetrievalChain

from langchain.memory import ConversationBufferWindowMemory

from langchain.document_transformers import LongContextReorder, EmbeddingsRedundantFilter

from langchain.retrievers.document_compressors import DocumentCompressorPipeline

from langchain.retrievers import ContextualCompressionRetriever

from langchain.embeddings import OpenAIEmbeddings

from langchain.chat_models import ChatOpenAI

from langchain.llms import OpenAI

import openai

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import os

from langchain.vectorstores import FAISS

from langchain.callbacks import OpenAICallbackHandler

from datetime import datetime

import chainlit as cl

from chainlit.input_widget import Select, Slider

import textwrap

import constants

from langchain.prompts import (

ChatPromptTemplate,

PromptTemplate,

SystemMessagePromptTemplate,

AIMessagePromptTemplate,

HumanMessagePromptTemplate,

)

from langchain.schema import (

AIMessage,

HumanMessage,

SystemMessage

)

I will go through the various things that we import from top to bottom.

The ConversationalRetrievalChain is a type of chain (imported from LangChain) that does most of the heavy lifting for us when it comes to retrieval augmentation. We can include a vector store in this chain, which will be used to retrieve fragments of information that we want to include as context in our questions to the LLM. There is also ‘RetrievalChain’ that does just that. What the ConversationalRetrievalChain adds to this is a chat history, so that we can actually have a conversation with an LLM that then memorizes earliers parts of the conversation. See the LangChain docs on the ConversationalRetrievalChain here.

To enable an LLM to memorize our conversation, we also need a memory object that we include in our chain. The ConversationBufferWindowMemory is one of several memory objects that langchain offers. We need one of those to store the chat history of our conversation, so that the LLM that we interact with has access to that history. The ConversationBufferWindowMemory is a kind of sliding window memory that memorizes a limited part of the conversation (see the docs here). This allows our tool to memorize the most recent interactions, without that memory getting too large for our LLM to handle (without exceeding the available context window of the model).

We also import various modules that include utilities that we use to process the fragments that our ConversationalRetrievalChain retrieves. The background to the LongContextReorder object could be the topic of its own blog post. It goes back to a finding that is discussed in this paper, which is that LLMs that are given a long context (basically the information included with the question), tend to get ‘lost in the middle’: They pay more attention to the information that is either in the beginning of the context, or at the end of the context, and information in the middle is not given as much consideration. The LongContextReorder object helps us order the retrieved fragments such that the fragments that it considers to be most important tend to be at the beginning or at the end of the collection of retrieved fragments. The EmbeddingsRedundantFilter filters out redundant fragments if we have multiple fragments that semantically are highly similar. Given that we have only a limited context window to work with, this object helps us to ensure that this context window is not filled with a lot of redundant information. The DocumentCompressorPipeline is an object that allows us to combine these different types of filters in a pipeline. The ContextualCompressionRetriever then allows us to integrate that pipeline in our retrieval chain. It is the retriever that we will integrate into our ConversationalRetrievalChain.

To be able to access OpenAI’s chat models, we import the ChatOpenAI module from the LangChain framework. We also need to use functions from the OpenAI module, so we import that as well. Given that we are working with OpenAI models, we need to import the openai module from OpenAI itself too. We then import the constants module, which is simply the other Python file in our main folder; the file in which we store our OpenAI API key. The dotenv module allows us to set environment variables, which we use in our script to set our OpenAI API key as an environment variable. We also need the os module to set our environment variable.

The literature that we wish to chat about is recorded in a FAISS vector store, so we’ll have to import the corresponding module to be able to use it. We also need to import the OpenAIEmbeddings module because when we retrieve fragments from our vector stores, we need to indicate the embeddings model that we used to create the embeddings.

To be honest, I do not know a lot about callback handlers. They are apparently functions that are executed in response to specific events or conditions in asynchronous or event-driven programs. To the best of my knowledge, we need a callback handler because our Chainlit-powered app will make use of asynchronous programming. In our case, we specifically need the OpenAICallbackHandler, so we import the corresponding module.

The datetime module allows us to get the current date and time, which we will use in the log files that we write to our answers folder for fact checking (see the section on folder structure above).

Since we are building a Chainlit-powered app, we also import the chainlit module. We then import various input widgets from the chainlit module that allow us to set various settings for our app in the browser interface. We will not be doing that much with these settings in this particular example, but in examples that I will discuss in future posts, the ability to change settings on the fly is important.

The remaining imports that we do are all related to prompt templates. As described in the LangChain documentation, prompt templates “are pre-defined recipes for generating prompts for language models”. As you’ll see in the example below, it allows us to predefine a prompt for the LLMs that we interact with. In the prompt template we can also include variables, which allows us ‘dynamically’ insert things in our prompt, such as the question that we asked and the context to that question that consists of the fragments of text we retrieve from our vector store. Since our desire is to develop a chat app, we need to use templates that have been specifically designed for chat purposes. These templates make use of various schemas that we also need to import.

Setting things up

The remainder of the script consists of four chunks:

- A chunk that is run when we start the app and in which we do some setup.

- A chunk that is run when we start a new chat (this does not have to mean that we restart the app).

- A chunk that is run when we update our chat settings (again, not something that we’ll discuss in detail here, but that we will discuss in more detail in a future post).

- A chunk that is run when we send a message to the LLM that we are chatting with.

Let’s start with the setting up chunk:

# Cleanup function for source strings

def string_cleanup(string):

"""A function to clean up strings in the sources from unwanted symbols"""

return string.replace("{","").replace("}","").replace("\\","").replace("/","")

# Set OpenAI API Key

load_dotenv()

os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"] = constants.APIKEY

openai.api_key = constants.APIKEY

# Load FAISS database

embeddings = OpenAIEmbeddings()

db = FAISS.load_local("./vectorstore/", embeddings)

# Set up callback handler

handler = OpenAICallbackHandler()

# Set memory

memory = ConversationBufferWindowMemory(memory_key="chat_history", input_key='question', output_key='answer', return_messages=True, k = 3)

# Customize prompt

system_prompt_template = (

'''

You are a knowledgeable professor working in academia.

Using the provided pieces of context, you answer the questions asked by the user.

If you don't know the answer, just say that you don't know, don't try to make up an answer.

"""

Context: {context}

"""

Please try to give detailed answers and write your answers as an academic text, unless explicitly told otherwise.

Use references to literature in your answer and include a bibliography for citations that you use.

If you cannot provide appropriate references, tell me by the end of your answer.

Format your answer as follows:

One or multiple sentences that constitutes part of your answer (APA-style reference)

The rest of your answer

Bibliography:

Bulleted bibliographical entries in APA-style

''')

system_prompt = PromptTemplate(template=system_prompt_template,

input_variables=["context"])

system_message_prompt = SystemMessagePromptTemplate(prompt = system_prompt)

human_template = "{question}"

human_message_prompt = HumanMessagePromptTemplate.from_template(human_template)

chat_prompt = ChatPromptTemplate.from_messages([system_message_prompt, human_message_prompt])

# Set up retriever

redundant_filter = EmbeddingsRedundantFilter(embeddings=embeddings)

reordering = LongContextReorder()

pipeline = DocumentCompressorPipeline(transformers=[redundant_filter, reordering])

retriever= ContextualCompressionRetriever(

base_compressor=pipeline, base_retriever=db.as_retriever(search_type="similarity_score_threshold", search_kwargs={"k" : 20, "score_threshold": .75}))

# Set up source file

now = datetime.now()

timestamp = now.strftime("%Y%m%d_%H%M%S")

filename = f"answers/answers_{timestamp}.org"

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.write("#+OPTIONS: toc:nil author:nil\n")

file.write(f"#+TITLE: Answers and sources for session started on {timestamp}\n\n")

You’ll see that this chunk starts with the definition of a function that removes various characters from strings that you pass it. I wrote this function to clean up the strings that I have the app write to a log to report its sources (the log that is stored in the answers folder). The part of the script where these strings are created are shown further below. Basically, these strings are reconstructed from the metadata that the ConversationalRetrievalChain extracts from the fragments that it retrieves. These bits of metadata originate from the bibtex entries of my Zotero library (see my first post). Given that they these bits of metadata often contain characters that make them look messy, I created the string_cleanup function to tidy them up a bit.

After defining this function we do some basic setting up. We first set our OpenAI API key as an environment variable and we make the openai module aware of our API key as well. We then load the OpenAIEmbeddings model, which is currently the text-embedding-ada-002 model. We need to pass this model as an argument when loading our vector store. By doing so, we clarify what type of embeddings are stored in the vector store, so that we can make use of them. We then load the actual vector store itself and store it in an object we simply call db. We then set up our callback handler. Finally, we set up our ConversationBufferWindowMemory. We need to tell it about the keys by which we identify our chat history, our questions and the output of the model after answering our questions. We can set the window size of the memory with the k argument, which in this example is set to three. This means it will remember up to three messages of conversation.

After this we write out our prompt template. You can see that we tell the LLM to assume a certain role and that we offer instructions on how to respond. I do not have a lot of experience with prompt engineering yet, so this prompt template probably can be improved. Also notice that I include one variable in this template, which is called context. This context consists of the retrieved fragments of text associated with our question. After writing out the prompt template, we create the actual template and relate our context variable to it. We then specify that this is the system message template. We create a separate template for the human messages, which simply consist of our question variable. We then create a chat prompt from the system message template and the human message template. We will later include this last prompt in our ConversationalRetrievalChain.

Next, we set up our retriever. We first set up the redundancy filter and then the LongContextReorder object. We combine these in a pipeline, which is itself included in a ContextualCompressionRetriever, along with the vector store, which acts as our ‘base retriever’. It is possible to simply use the vector store as a retriever directly, but then we would not have the benefits that the redundancy filter and LongContextReorder object give us. We pass several arguments to our base retriever, namely:

- an argument that indicates we want to use a similarity score threshold to select documents;

- the number of documents to retrieve (

k); - the similarity score threshold, which is the minimum similarity score that a fragment of text should have to be considered for retrieval.

Twenty fragments is a pretty large number of fragments to retrieve, given that we work with a limited context window and given that longer contexts also have the unfortunate consequence that not all of it will be equally considered by the LLM. However, I have set this relatively high number because we also do some filtering and reordering as part of our pipeline, which compensates somewhat from the downsides of retrieving many fragments. We will later integrate our ContextualCompressionRetriever in our ConversationalRetrievalChain.

The last thing we do in this chunk of the script is to set up the log file that we wish to write to the answers folder. I opted to use org files for this, since I work a lot with org files in general. We give the file a filename that includes a timestamp and we write a header and a title to the file itself. We will populate it further during our conversation with the LLM.

Chat start and chat settings update

The next chunk of our script is a shot one:

# Prepare settings

@cl.on_chat_start

async def start():

settings = await cl.ChatSettings(

[

Select(

id="Model",

label="OpenAI - Model",

values=["gpt-3.5-turbo-16k", "gpt-4", "gpt-4-32k"],

initial_index=0,

),

Slider(

id="Temperature",

label="OpenAI - Temperature",

initial=0,

min=0,

max=2,

step=0.1,

),

]

).send()

await setup_chain(settings)

In this chunk we define the chat settings that the user can change on the fly, which is a feature of chainlit apps. In this case we allow the user to select different types of models that OpenAI has on offer through its API. I default to the gpt-3.5-turbo-16k model, because it is still relatively cheap and has a longer context window than the gpt-3.5-turbo model. I have found that, with the number of fragments that I retrieve, this longer context window is often necessary. The user can also set temperature for the model, which controls how deterministic its answers will be: A higher temperature will allow for more variability in answers.

We could include more settings if we wanted. For example, in another, more elaborate tool that I made, I also allow the user to set the number of text fragments retrieved by the base retriever. It should also be possible to control the size of the memory window using chat settings.

The next chunk of the script is called whenever one of the above chat settings is changed, but it is also run the outset, when a new chat is started:

# When settings are updated

@cl.on_settings_update

async def setup_chain(settings):

# Set llm

llm=ChatOpenAI(

temperature=settings["Temperature"],

model=settings["Model"],

)

# Set up conversational chain

chain = ConversationalRetrievalChain.from_llm(

llm=llm,

retriever=retriever,

chain_type="stuff",

return_source_documents = True,

return_generated_question = True,

combine_docs_chain_kwargs={'prompt': chat_prompt},

memory=memory,

condense_question_llm = ChatOpenAI(temperature=0, model='gpt-3.5-turbo'),

)

cl.user_session.set("chain", chain)

Here, we first specify the LLM that we will be conversing with. As you can see, the parameters of this model are retrieved from the chat settings, namely the model name and its temperature.

We then finally get to setting up the ConversationalRetrievalChain. We clarify what LLM we wish to converse with. We then tell the chain what retriever we will be using (our ContextualCompressionRetriever). We also define how our documents are integrated in the context variable of our prompts, for which the LangChain framework offers several options. I use the simplest one, ‘stuff documents’, which basically stuffs also retrieved fragments in the context. The other options usually involve iterating over our fragments in different ways. This is more time consuming and it often involves additional calls to LLMs, which makes them more expensive options. So far, I have not seen great benefit from using any of these other options. We tell the chain to also return the ‘source documents’, which allows us to access the actual fragments of text that our retriever retrieves. We need to do this if we want to enable our tool to report its sources in the log file that we have it create. For similar reasons, we also tell the chain to retun the question that it generated. We then specify the prompt that we want the chain to use, which is the chat prompt we created earlier. We also specify the memory object that the chain can use to memorize our conversation, such that we can have an actual conversation with the LLM. Finally, in this we case we also specify the model that the chain can use to condense questions (which is something it apparently always does). By default, it will use the model that we set with the llm parameter, but I force it to use the gpt-3.5-turbo model, because it is unnecessary to use a more expensive model for this.

So now we have our ConversationalRetrievalChain all set up!

Messages

The last chunk of our script basically handles what happens when messages are being sent to an LLM:

@cl.on_message

async def main(message: str):

chain = cl.user_session.get("chain")

cb = cl.LangchainCallbackHandler()

cb.answer_reached = True

res = await cl.make_async(chain)(message.content, callbacks=[cb])

question = res["question"]

answer = res["answer"]

answer += "\n\n Sources:\n\n"

sources = res["source_documents"]

print_sources = []

with open(filename, 'a') as file:

file.write("* Query:\n")

file.write(question)

file.write("\n")

file.write("* Answer:\n")

file.write(res['answer'])

file.write("\n")

counter = 1

for source in sources:

reference = "INVALID REF"

if source.metadata.get('ENTRYTYPE') == 'article':

reference = (

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('author', "")) + " (" +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('year', "")) + "). " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('title', "")) + ". " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('journal', "")) + ", " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('volume', "")) + " (" +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('number', "")) + "): " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('pages', "")) + ".")

elif source.metadata.get('ENTRYTYPE') == 'book':

author = ""

if 'author' in source.metadata:

author = string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('author', "NA"))

elif 'editor' in source.metadata:

author = string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('editor', "NA"))

reference = (

author + " (" +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('year', "")) + "). " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('title', "")) + ". " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('address', "")) + ": " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('publisher', "")) + ".")

elif source.metadata.get('ENTRYTYPE') == 'incollection':

reference = (

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('author', "")) + " (" +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('year', "")) + "). " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('title', "")) + ". " +

"In: " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('editor', "")) +

" (Eds.), " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('booktitle', "")) + ", " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('pages', "")) + ".")

else:

author = ""

if 'author' in source.metadata:

author = string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('author', "NA"))

elif 'editor' in source.metadata:

author = string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('editor', "NA"))

reference = (

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('author', "")) + " (" +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('year', "")) + "). " +

string_cleanup(source.metadata.get('title', "")) + ".")

if source.metadata['source'] not in print_sources:

print_sources.append(source.metadata['source'])

answer += '- '

answer += reference

answer += '\n'

file.write(f"** Document_{counter}:\n- ")

file.write(reference)

file.write("\n- ")

file.write(os.path.basename(source.metadata['source']))

file.write("\n")

file.write("*** Content:\n")

file.write(source.page_content)

file.write("\n\n")

counter += 1

await cl.Message(content=answer).send()

This chunk is pretty lengthy, but much of it is a somewhat convoluted way of having the tool report its sources, both in is responses to the user, but also in the log file that we write to the answers folder.

The chunk more or less starts with a specification of the chain that we are using (the one we just created). We then define our callback handler. The res object is what we store the response of the LLM in. It consists of several parts, including the question that we asked (remember that we told our ConversationalRetrievalChain to return the question), the answer to our question, and the source documents.

As you can see, we extend the original answer of the model with a list of our sources. Most of what you see in the remainder of the chunk are different approaches to formatting these sources, depending on the type of source it is. We retrieve various metadata from our sources to format the actual references. As mentioned before, we also include these references in our log file, along with our question and the answer that the LLM gave us.

A short demonstration

Now that we have our complete script, let us actually use it.

We can start our chainlit app by going to its main folder and typing the following command:

chainlit run ask_cl.py

This will open a browser window in which we are greated with a default readme file (the chainlit.md file). As mentioned previously, we can change this file as we wish. My version of the tool looks as shown in the picture below.

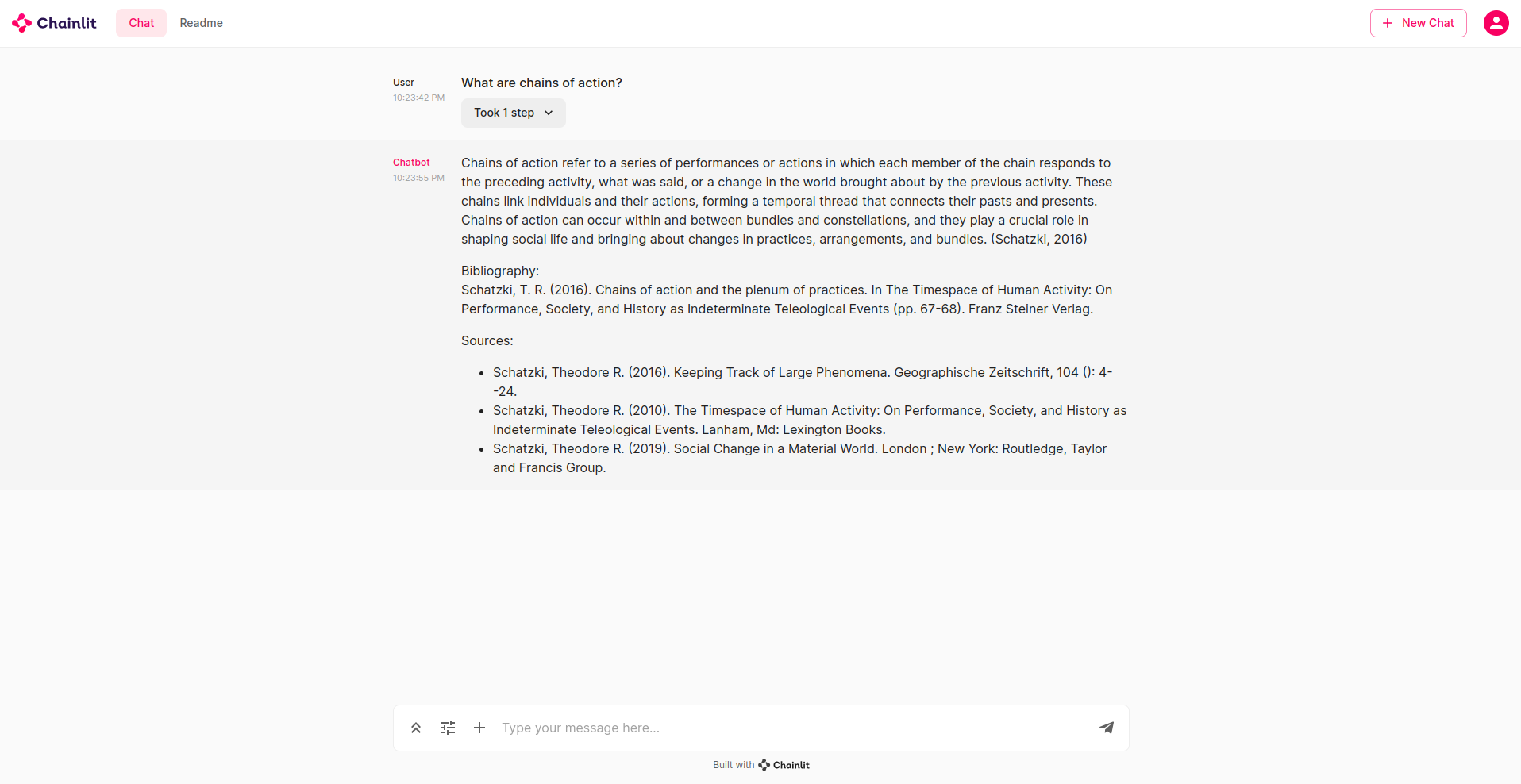

We can now start asking our app questions. In the example shown below, I asked the app what “chains of action” are, a concept used by Theodore Schatzki in his version of social practice theories. The answer that we get is pretty good. Also notice how the app reports the sources it consulted, which are papers that I have in my Zotero library.

Let us also take a look at part of the answer file that has been created and populated in the meantime:

#+OPTIONS: toc:nil author:nil

#+TITLE: Answers and sources for session started on 20231023_222003

* Query:

What are chains of action?

* Answer:

Chains of action refer to a series of performances or actions in which each member of the chain responds to the preceding activity, what was said, or a change in the world brought about by the previous activity. These chains link individuals and their actions, forming a temporal thread that connects their pasts and presents. Chains of action can occur within and between bundles and constellations, and they play a crucial role in shaping social life and bringing about changes in practices, arrangements, and bundles. (Schatzki, 2016)

Bibliography:

Schatzki, T. R. (2016). Chains of action and the plenum of practices. In The Timespace of Human Activity: On Performance, Society, and History as Indeterminate Teleological Events (pp. 67-68). Franz Steiner Verlag.

** Document_1:

- Schatzki, Theodore R. (2016). Keeping Track of Large Phenomena. Geographische Zeitschrift, 104 (): 4--24.

- Schatzki_2016_Geographische Zeitschrift.txt

*** Content:

(7) Interactions, as noted, form one sort of action chain, namely, those encompassing reciprocal reactions by two or more people. Subtypes include exchange,

teamwork, conversation, communication, and the transmission of information. (These concepts can also be used to name nexuses of chains: compare two

people exchanging presents in person to two tribes exchanging gifts over several months.) Other types of chain are imitation (in a more intuitive sense than

Tarde’s ubiquitous appropriation) and governance (intentional shaping and influencing). Beyond these and other named types of chains, social life houses an

immense number of highly contingent and haphazard chains of unnamed types

that often go uncognized and unrecognized yet build a formative unfolding rhizomatic structure in social life.

4. Chains of Action and the Plenum of Practices

Individualists can welcome the idea of action chains. Indeed, unintentional consequences of action, the existence of which is central to the individualist outlook, can

be construed as results of action chains. Contrary to individualists, however, practice

theorists do not believe that action chains occur in a vacuum, less metaphorically, that

they occur only in a texture formed by more individuals and their actions. Rather,

chains transpire in the plenum of practices. This implies that they propagate within

and between bundles and constellations.

** Document_2:

- Schatzki, Theodore R. (2010). The Timespace of Human Activity: On Performance, Society, and History as Indeterminate Teleological Events. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books.

- Schatzki_2010_The timespace of human activity.txt

*** Content:

The second type of sinew embraces chains of action. Lives hang together

when chains of action pass through and thereby link them. A chain of ac-

tion is a series of performances, each member of which responds either to

the preceding activity in the series, to what the previous activity said, or to a

change in the world that the preceding activity brought about. For example,

when a person taking a horse farm tour drops a map on the ground, and the

tour leader picks it up and puts it in a trash receptacle, their lives are linked

Activity Timespace and Social Life 67

by a chain of action (which also connects them to the people who installed

the receptacle). Conversations, to take another example, are chains of action

in which people respond to what others say or to the saying of it. Chains of

action are configurations of interwoven temporality. For responding to an

action, to something said, or to a change in the world is the past dimension of

activity. Each link in a chain of action thus involves some person’s past, and

a chain comprising multiple links strings together the pasts and presents of

different people.

You can see that it lists my question, the answer that I was given, and the various fragments of text on which the answer was based. This not only allows us to double check the answers that I got, but also to quickly identify parts of different papers that we might want to look into more.

Just the beginning

I hope this post is useful to people that would like to build something similar themselves. The app described in this post builds on one of the first LangChain tools that I developed (I did do a lot of fine-tuning of it over time). It has been incredibly useful for me, but it has more or less become redundant after I started developing an agent that I can use to not only chat about my literature, but also for various other things. This includes retrieving information from empirical sources (e.g., news archives) and then relating conceptual knowledge to that empirical information. I will go into the use of agents in future posts.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: